How Many Offspring (Babies) Do They Usually Produce at One Time?

Lambing: the mother licks the first lamb while giving nativity to the second

Nascency is the act or procedure of begetting or bringing forth offspring,[1] too referred to in technical contexts as parturition. In mammals, the procedure is initiated by hormones which cause the muscular walls of the uterus to contract, expelling the fetus at a developmental stage when information technology is ready to feed and breathe.

In some species the offspring is precocial and can motility around almost immediately after nativity only in others information technology is altricial and completely dependent on parenting.

In marsupials, the fetus is built-in at a very immature stage after a short gestational period and develops farther in its mother'south womb'due south pouch.

It is non only mammals that requite birth. Some reptiles, amphibians, fish and invertebrates comport their developing immature inside them. Some of these are ovoviviparous, with the eggs being hatched within the mother'south body, and others are viviparous, with the embryo developing inside her body, every bit in the case of mammals.

Mammals [edit]

Large mammals, such as primates, cattle, horses, some antelopes, giraffes, hippopotamuses, rhinoceroses, elephants, seals, whales, dolphins, and porpoises, by and large are pregnant with ane offspring at a fourth dimension, although they may take twin or multiple births on occasion.

In these large animals, the birth process is similar to that of a human, though in almost the offspring is precocial. This means that it is born in a more advanced country than a human baby and is able to stand, walk and run (or swim in the case of an aquatic mammal) before long after nativity.[2]

In the case of whales, dolphins and porpoises, the single calf is normally born tail first which minimizes the risk of drowning.[3] The female parent encourages the newborn calf to rise to the surface of the water to breathe.[4]

Most smaller mammals accept multiple births, producing litters of young which may number twelve or more. In these animals, each fetus is surrounded by its own amniotic sac and has a separate placenta. This separates from the wall of the uterus during labor and the fetus works its fashion towards the nativity canal.[ citation needed ]

Large mammals which requite nativity to twins is much more rare, simply information technology does occur occasionally even for mammals as big every bit elephants. In April 2018, approximately 8-month old elephant twins were sighted joining their female parent's herd in the Tarangire National Park of Tanzania, estimated to have been born in August 2017.[5]

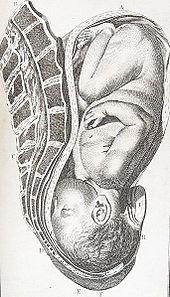

Human being childbirth [edit]

Humans usually produce a single offspring at a fourth dimension. The mother'due south body is prepared for nascency by hormones produced by the pituitary gland, the ovary and the placenta.[2] The full gestation period from fertilization to birth is normally about 38 weeks (nascence usually occurring 40 weeks after the final menstrual period). The normal process of childbirth takes several hours and has three stages. The first stage starts with a serial of involuntary contractions of the muscular walls of the uterus and gradual dilation of the neck. The active phase of the showtime stage starts when the cervix is dilated more most 4 cm in diameter and is when the contractions become stronger and regular. The caput (or the buttocks in a breech birth) of the babe is pushed against the cervix, which gradually dilates until is fully dilated at 10 cm diameter. At some time, the amniotic sac bursts and the amniotic fluid escapes (too known as rupture of membranes or breaking the water).[6] In stage two, starting when the cervix is fully dilated, strong contractions of the uterus and agile pushing by the mother expels the infant out through the vagina, which during this stage of labour is called a birth canal as this passage contains a baby, and the babe is born with umbilical cord attached.[7] In stage three, which begins subsequently the birth of the baby, further contractions expel the placenta, amniotic sac, and the remaining portion of the umbilical cord normally inside a few minutes.[8]

Enormous changes take place in the newborn's circulation to enable breathing in air. In the uterus, the unborn baby is dependent on circulation of claret through the placenta for sustenance including gaseous exchange and the unborn baby's blood bypasses the lungs by flowing through the foramen ovale, which is a pigsty in the septum dividing the correct atrium and left atrium. After nascency the umbilical string is clamped and cut, the baby starts to breathe air, and blood from the right ventricle starts to catamenia to the lungs for gaseous exchange and oxygenated blood returns to the left atrium, which is pumped into the left ventricle, and then pumped into the principal arterial organization. As a result of these changes, the blood pressure level in the left atrium exceeds the pressure in the right atrium, and this pressure difference forces the foramen ovale to close separating the left and correct sides of the middle. The umbilical vein, umbilical arteries, ductus venosus and ductus arteriosus are not needed for life in air and in time these vessels become ligaments (embryonic remnants).[9]

Cattle [edit]

Birthing in cattle is typical of a larger mammal. A moo-cow goes through three stages of labor during normal commitment of a dogie. During stage 1, the animal seeks a quiet place away from the rest of the herd. Hormone changes cause soft tissues of the birth canal to relax as the mother's body prepares for birth. The contractions of the uterus are non obvious externally, simply the cow may be restless. She may announced agitated, alternate between continuing and lying down, with her tail slightly raised and her back arched. The fetus is pushed toward the birth culvert by each wrinkle and the cow'south neck gradually begins to dilate. Stage one may last several hours, and ends when the cervix is fully dilated. Phase two can be seen to be underway when there is external protrusion of the amniotic sac through the vulva, closely followed by the appearance of the calf'southward front hooves and head in a front presentation (or occasionally the dogie'due south tail and rear end in a posterior presentation).[10] During the second stage, the cow will usually lie downwards on her side to button and the calf progresses through the birth culvert. The complete delivery of the calf (or calves in a multiple birth) signifies the end of stage ii. The cow scrambles to her feet (if lying down at this stage), turns circular and starts vigorously licking the calf. The dogie takes its beginning few breaths and inside minutes is struggling to rise to its feet. The third and final phase of labor is the delivery of the placenta, which is normally expelled within a few hours and is oftentimes eaten past the unremarkably herbivorous cow.[x] [eleven]

Dogs [edit]

Birth is termed whelping in dogs.[12] Among dogs, equally whelping approaches, contractions become more frequent. Labour in the bitch can be divided into iii stages. The first stage is when the cervix dilates, this causes discomfort and restlessness in the bowwow. Common signs of this stage are panting, fasting, and/or vomiting. This may last up to 12hrs.[12] Phase two is the passage of the offspring.[12] The amniotic sac looking similar a glistening grey airship, with a puppy inside, is propelled through the vulva. Later on further contractions, the sac is expelled and the bowwow breaks the membranes releasing clear fluid and exposing the puppy. The mother chews at the umbilical cord and licks the puppy vigorously, which stimulates it to exhale. If the puppy has non taken its first jiff within about six minutes, it is probable to die. Further puppies follow in a like way one by one usually with less straining than the first unremarkably at 15-60min intervals. If a pup has not been passed in 2 hrs a veterinarian should be contacted.[12] Phase three is the passing of the placentas. This ofttimes occurs in conjunction with stage two with the passing of each offspring.[12] The mother will and so unremarkably swallow the afterbirth.[13] This is an adaption to go on the den clean and foreclose its detection by predators.[12]

Marsupials [edit]

A kangaroo joey firmly fastened to a nipple inside the pouch

An infant marsupial is built-in in a very immature land.[14] The gestation period is usually shorter than the intervals between oestrus periods. The first sign that a birth is imminent is the mother cleaning out her pouch. When information technology is built-in, the infant is pink, blind, furless and a few centimetres long. It has nostrils in order to exhale and forelegs to cling onto its mother's hairs simply its hind legs are undeveloped. It crawls through its mother'due south fur and makes its way into the pouch. Here information technology fixes onto a teat which swells inside its mouth. It stays attached to the teat for several months until it is sufficiently adult to emerge.[15] Joeys are born with "oral shields"; in species without pouches or with rudimentary pouches these are more developed than in forms with well-developed pouches, implying a part in maintaining the young attached to the female parent's nipple.[16]

Other animals [edit]

A Cladocera giving nascency (100x magnification)

Many reptiles and the vast majority of invertebrates, well-nigh fish, amphibians and all birds are oviparous, that is, they lay eggs with petty or no embryonic development taking identify within the mother. In aquatic organisms, fertilization is nearly always external with sperm and eggs being liberated into the water (an exception is sharks and rays, which have internal fertilization[17]). Millions of eggs may be produced with no farther parental interest, in the expectation that a small number may survive to become mature individuals. Terrestrial invertebrates may too produce large numbers of eggs, a few of which may avoid predation and behave on the species. Some fish, reptiles, and amphibians have adopted a different strategy and invest their effort in producing a small number of young at a more advanced stage which are more likely to survive to machismo. Birds treat their young in the nest and provide for their needs after hatching and it is perhaps unsurprising that internal development does not occur in birds, given their need to fly.[xviii]

Ovoviviparity is a manner of reproduction in which embryos develop inside eggs that remain in the female parent's body until they are ready to hatch. Ovoviviparous animals are like to viviparous species in that there is internal fertilization and the young are born in an avant-garde country, but differ in that there is no placental connectedness and the unborn young are nourished by egg yolk. The female parent's body provides gas exchange (respiration), but that is largely necessary for oviparous animals besides.[eighteen] In many sharks the eggs hatch in the oviduct within the mother's body and the embryos are nourished by the egg'southward yolk and fluids secreted by glands in the walls of the oviduct.[xix] The Lamniforme sharks practice oophagy, where the outset embryos to hatch consume the remaining eggs and sand tiger shark pups cannibalistically consume neighbouring embryos. The requiem sharks maintain a placental link to the developing young, this practice is known as viviparity. This is more coordinating to mammalian gestation than to that of other fishes. In all these cases, the young are born alive and fully functional.[20] The majority of caecilians are ovoviviparous and give birth to already developed offspring. When the young have finished their yolk sacs they feed on nutrients secreted past cells lining the oviduct and even the cells themselves which they eat with specialist scraping teeth.[21] The Alpine salamander (Salamandra atra) and several species of Tanzanian toad in the genus Nectophrynoides are ovoviviparous, developing through the larval phase within the mother'southward oviduct and eventually emerging as fully formed juveniles.[22]

A more developed course of viviparity called placental viviparity is adopted past some species of scorpions[23] and cockroaches,[24] sure genera of sharks, snakes and velvet worms. In these, the developing embryo is nourished by some form of placental construction. The earliest known placenta was found recently in a group of extinct fishes called placoderms. A fossil from Australia'south Gogo Formation, laid downward in the Devonian menstruation, 380 million years agone, was found with an embryo inside it connected by an umbilical cord to a yolk sac. The observe confirmed the hypothesis that a sub-group of placoderms, called ptyctodontids, fertilized their eggs internally. Some fishes that fertilize their eggs internally likewise give birth to alive young, as seen here. This discovery moved our knowledge of live nascency back 200 1000000 years.[25] The fossil of some other genus was found with three embryos in the aforementioned position.[26] Placoderms are a sister grouping of the ancestor of all living jawed fishes (Gnathostomata), including both chondrichthyians, the sharks & rays, and Osteichthyes, the bony fishes.

Among lizards, the viviparous lizard Zootoca vivipara, ho-hum worms and many species of skink are viviparous, giving birth to alive young. Some are ovoviviparous merely others such as members of the genera Tiliqua and Corucia, requite nativity to live young that develop internally, deriving their nourishment from a mammal-like placenta attached to the inside of the mother's uterus. In a recently described example, an African species, Trachylepis ivensi, has adult a purely reptilian placenta directly comparable in structure and office to a mammalian placenta.[27] Vivipary is rare in snakes, simply boas and vipers are viviparous, giving nascence to alive young.

Female person aphid giving nativity

The majority of insects lay eggs but a very few give nascency to offspring that are miniature versions of the adult.[18] The aphid has a circuitous life cycle and during the summer months is able to multiply with slap-up rapidity. Its reproduction is typically parthenogenetic and viviparous and females produce unfertilized eggs which they retain inside their bodies.[28] The embryos develop within their mothers' ovarioles and the offspring are clones of their mothers. Female nymphs are born which grow rapidly and soon produce more female person offspring themselves.[29] In some instances, the newborn nymphs already take developing embryos inside them.[18]

See as well [edit]

| | Wikiquote has quotations related to: Birth |

- Fauna sexual behaviour

- Convenance season

- Caesarean section

- Dystocia

- Episiotomy

- Foaling (horses)

- Forceps delivery

- Kegel exercises

- Mating system

- Odon device

- Perineal massage

- Reproduction

- Reproductive organisation

- Ventouse

- Nascence spacing

References [edit]

- ^ "nascency". OED Online. June 2013. Oxford University Printing. Entry 19395 (accessed 30 August 2013).

- ^ a b Dorit, R. 50.; Walker, W. F.; Barnes, R. D. (1991). Zoology. Saunders College Publishing. pp. 526–527. ISBN978-0-03-030504-7.

- ^ Mark Simmonds, Whales and Dolphins of the World, New Kingdom of the netherlands Publishers (2007), Ch. 1, p. 32 ISBN 1845378202.

- ^ Crockett, Gary (2011). "Humpback Whale Calves". Humpback whales Australia. Archived from the original on 2017-02-27. Retrieved 2013-08-28 .

- ^ "Trunk Twins : Elephant Twins Born in Tarangire | Asilia Africa". Asilia Africa. 2018-04-06. Retrieved 2018-04-06 .

- ^ Dainty (2007). Section 1.6, Normal labour: first stage

- ^ Squeamish (2007). Section 1.7, Normal labour: second stage

- ^ Prissy (2007). Section ane.8, Normal labour: third stage

- ^ Houston, Rob (editor); Lea, Maxine (art editor) (2007). The Man Body Book. Dorling Kindersley. p. 215. ISBN978-i-8561-3007-3.

- ^ a b "Calving". Alberta: Agriculture and Rural Development. 2000-02-01. Retrieved 2013-08-28 .

- ^ "Calving Management in Dairy Herds: Timing of Intervention and Stillbirth" (PDF). The Ohio State University College of Veterinarian Medicine Extension. 2012. Retrieved 2013-12-17 .

- ^ a b c d east f Kustritz, G. (2005). "Reproductive behaviour of small animals". Theriogenology. 64 (3): 734–746. doi:ten.1016/j.theriogenology.2005.05.022. PMID 15946732.

- ^ Dunn, T.J. "Whelping: New Puppies On The Way!". Puppy Eye. Pet MD. Retrieved 2013-08-28 .

- ^ Hugh Tyndale-Biscoe; Marilyn Renfree (30 January 1987). Reproductive Physiology of Marsupials. Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0-521-33792-2.

- ^ "Reproduction and evolution". Thylacine Museum. Retrieved 2013-08-28 .

- ^ Yvette Schneider Nanette (Aug 2011). "The evolution of the olfactory organs in newly hatched monotremes and neonate marsupials". J. Anat. 219 (two): 229–242. doi:x.1111/j.1469-7580.2011.01393.10. PMC3162242. PMID 21592102.

- ^ Sea World, Sharks & Rays Archived 2013-xi-x at the Wayback Machine; accessed 2013.09.09.

- ^ a b c d Attenborough, David (1990). The Trials of Life. pp. 26–xxx. ISBN9780002199124.

- ^ Adams, Kye R.; Fetterplace, Lachlan C.; Davis, Andrew R.; Taylor, Matthew D.; Knott, Nathan A. (Jan 2018). "Sharks, rays and abortion: The prevalence of capture-induced parturition in elasmobranchs". Biological Conservation. 217: 11–27. doi:x.1016/j.biocon.2017.10.010. Archived from the original on 2019-02-23. Retrieved 2019-06-30 .

- ^ "Birth and care of young". Animals: Sharks and rays. Busch Entertainment Corporation. Archived from the original on August 3, 2013. Retrieved 2013-08-28 .

- ^ Stebbins, Robert C.; Cohen, Nathan Westward. (1995). A Natural History of Amphibians. Princeton University Printing. pp. 172–173. ISBN978-0-691-03281-8.

- ^ Stebbins, Robert C.; Cohen, Nathan W. (1995). A Natural History of Amphibians. Princeton University Press. p. 204. ISBN978-0-691-03281-eight.

- ^ Capinera, John Fifty., Encyclopedia of entomology. Springer Reference, 2008, p. 3311.

- ^ Costa, James T., The Other Insect Societies. Belknap Press, 2006, p. 151.

- ^ Dennis, Carina (2008-05-28). "Nature News: The oldest pregnant mum: Devonian fossilized fish contains an embryo". Nature. 453 (7195): 575. Bibcode:2008Natur.453..575D. doi:10.1038/453575a. PMID 18509405.

- ^ Long, John A.; Trinastic, Kate; Immature, Gavin C.; Senden, Tim (2008-05-28). "Live birth in the Devonian menstruum". Nature. 453 (7195): 650–652. Bibcode:2008Natur.453..650L. doi:ten.1038/nature06966. PMID 18509443. S2CID 205213348.

- ^ Blackburn DG, Flemming AF (2012). "Invasive implantation and intimate placental associations in a placentotrophic African cadger, Trachylepis ivensi (scincidae)". J. Morphol. 273 (2): 137–59. doi:10.1002/jmor.11011. PMID 21956253. S2CID 5191828.

- ^ Blackman, Roger L (1979). "Stability and variation in aphid clonal lineages". Biological Journal of the Linnean Guild. 11 (3): 259–277. doi:x.1111/j.1095-8312.1979.tb00038.ten. ISSN 1095-8312.

- ^ Conrad, Jim (2011-12-10). "The aphid life cycle". The Backyard Nature Website. Retrieved 2013-08-31 .

Cited texts [edit]

- "Intrapartum care: Intendance of healthy women and their babies during childbirth". Nice. September 2007. Archived from the original on 2014-04-26.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Birth#:~:text=Large%20mammals%2C%20such%20as%20primates,or%20multiple%20births%20on%20occasion.

0 Response to "How Many Offspring (Babies) Do They Usually Produce at One Time?"

Post a Comment